At the scene / Alongside

Gunter Breckner

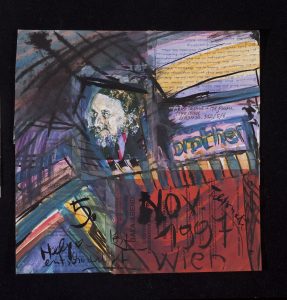

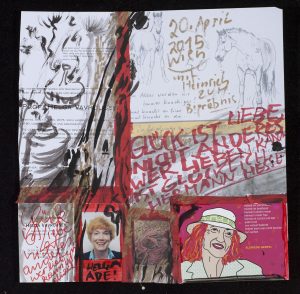

For almost 20 years Linde has persisted in completing “Tageszeichnungen”, which are daily productions in a fixed format of about 35cm by 35cm, and over the last 16 years I myself have been the occasional subject of the series. The main feat for Linde is that each piece is completed before she goes to sleep, to make sure that it counts for the day. So it can happen that an anguished cry rings out at midnight: “I haven’t done my Tageszeichnung today!”, and then she gets to work. She draws from a wide range of techniques for these daily creations, but they are held together by some common threads. In addition to the fixed format, these include information such as date and location, as well as notes on experiences and emotions. These are added at the end, providing an element of closure to the process. Most often she sketches out some essential aspect of the immediate surroundings on Japanese Washi paper using pigmented ink, watercolor, markers, or pastels. Whatever materials she has available shape the final appearance of the picture. For example, one of the daily pictures from a few years ago is graphically very unusual because there were no brushes handy during a drive to Hungary – Linde resolutely painted with leaves of grass. Sometimes she uses clippings from current exhibition posters or announcements as the base for a picture. Often she also incorporates memorabilia such as invitations, tickets, notes, letters, or postcards (many from other visual artists or writers) into a collage which becomes part of the drawing, and sometimes I contribute press clippings. As a series, these daily pictures convey the dynamic essence of Linde’s daily life, her many interests and activities, her travels and her extended stays abroad. Many of the Tageszeichnungen originate on the sidelines of some social occasion, such as a vernissage or party, and contain signatures or comments from the participating friends and aquaintances. Guests in Linde’s studio are often coaxed, under gentle pressure, to add a little drawing next to their signature, before “being allowed” to leave, resulting in interesting collaborations.

The “Atelierzeichnungen” (studio pictures) form another series, started in 1982. These are mostly done on paper, in a 64cm by 48cm format. In this series, Linde captures studios and workspaces, almost exclusively of other artists from her large circle of friends. This personal connection to the artist is an important element, because it shapes the work before the first line is even drawn. She sits unobtrusively, but intensely concentrated, in a corner painting and drawing. In quick succession, typically starting at one edge and resolutely filling the sheet, the essential features and furnishings of the room take shape – often in Linde’s characteristic fisheye perspective, with bent and plunging lines around the focus of the picture. It really surprised me, for example, when Linde started a picture of Rudolf Hradil’s studio in Salzburg with the bullseye of a washing machine and then let the rest grow from there. With great inventiveness Linde pushes beyond the restrictions of the limited array of utensils that she brings along to each of these visits (e.g. charcoals, pastels, pigmented inks, or watercolors) and creates astounding effects through wiping, scraping, scratching, or sprinkling: The colors of the furniture, and even of pictures hanging in the studio, are captured unerringly. Essential elements are reflected in great detail, so accurately in fact that even Chinese and Japanese calligraphy is legible (as I recently discovered in Japan). The atmosphere of the room and its contents is just as palpable as the “aura” of the artist who creates there. I witnessed this process over and over again: Nali Gruber, Othmar Schmiderer, Armin Pramstaller, Franz Josef Altenburg, and in my own studio.

Linde works in “Mixed Media” at any time and in any place: in her garden in Zwettl, in the Salzkammergut (an alpine resort area in Austria), in the ski resorts, while traveling and during stays in Paris, Scotland, Egypt and the Canary Islands, Namibia and South Africa, etc., while vacationing on a sailboat in the Caribbean and during study trips to China, Tibet, and Japan. Even during ski vacation it’s important that the hotel room has a “paintable” view. Toothbrush tumblers, ash trays, and the like, are commandeered for mixing pigmented inks or watercolors, and many a hotel sink has been stained. The ink bottles, frequently leaking into the luggage, present another challenge during travels. Linde doesn’t like it when other people try to glance over her shoulder while she’s painting, and she usually manages to find a quiet nook where impressive paintings or daily drawings develop – even in tourist-infested hotspots like the park of Versailles, the pyramids of Gizah, the Potala Palace in Lhasa, the forbidden city in Beijing, or the temples and shrines of Japan. It’s the opposite during our Caribbean sailing trips on the yacht of my brother Fritz, where a full-fledged studio is set up on the white deck, leaving stains that would really tick off any other boat owner. Any ocean creature that we catch, be it fish or lobster, has to be painted before we can chuck it into the frying pan. They are draped somewhere in the cockpit or on deck, often intermingled with boating equipment or diving gear, and artistically documented on different formats ranging from postcard-sized plain paper to large sheets which have been colorfully glazed back in Vienna. During dinner Linde switches to the short series of “Cooking Strips” (e.g. see “Fish Poem”, Mandelbaum Verlag 2004): On previously prepared strips of paper the daily menu, and sometimes its preparation, is captured – always a precarious balancing act while eating at the same time before the food gets cold. In between swimming, snorkeling, and sailing, Linde paints the palm-covered islands from the boat, or she packs her utensils into the dinghy and heads to the beach: While we sweatily pass the noon heat in the shade or bathe in the cooling ocean, Linde sits with her sun hat on a portable stool (which causes all kinds of troubles at airport security!) and paints for hours full of concentration and without any sign of exhaustion. I like to remember one particular scene in the Las Aves archipelago of Venezuela: We were scouting on the dinghy through mangrove forests inhabited by innumerable seabirds, and Linde captured the breeding or fleeing birds with ink on post-card sized paper faster than I could focus my camera and hit the shutter button. The same is true in the dark of a goat stable on the Grafenberg Alm in Styria: While I am trying, in vain, to get a proper picture of Bodo Hell milking a goat, Linde has quickly captured the situation with a few strokes of a brush.

The genesis of Linde’s Oil and Tempera Paintings is, however, very different. They are created almost exclusively in her house and garden in Zwettl, which also serves as a retreat for inner regeneration. Guests are only rarely received, except for the annual summer fête. The majority of paintings are done during the warm season in the garden or studio, often in highly focused bursts of work. Around 1994, in the early stages of our relationship, I wanted to call Linde in Zwettl. Not knowing her routine, I waited impatiently until early evening to avoid disturbing her painting. Her mother Karla picked up the phone and brushed me off, with a smug undertone in her voice: “… what did I think?. Linde had just started painting in the garden a short while ago! She’d only really get into it as dusk slowly settled in, and would keep going until it was completely dark. I should call back when it was pitch dark for quite a while, then she’d probably come back into the house.

Since then, I ‘ve been privileged to experience the creation of several oil paintings. Linde chooses a focal point somewhere in the garden and starts on a canvas attached to a board, not a stretcher frame. When a painting approaches some level of completion, it moves to the studio, leaning against a wall or pinned onto a board, for a period of reflection and tweaking. Once it is considered complete, it moves further up into the attic for drying. Around 2002 the technique and contents changed: The canvas is prepped with a mix of sand and binder in different shapes and thicknesses to create a three-dimensional base structure on which pictures of the garden, or from travel memories, take shape. Old pictures, magazine pages, or other finds from the attic sometimes become part of a collage, to be painted over later. The house has been with the family for three generations, and has accumulated nearly a century’s worth of chattels and knick-knacks, magazines and clothing, and antiques passionately collected by Karla, the mother. A direct link to the garden is often not present anymore in the composition of the paintings. After a journey, impressions of the garden are mirrored in various patterns from ocean floors and coral reefs (memories from snorkeling in the Caribbean), or confronted with the calligraphy, landscapes, and rock formations of China or Japan. The new technique requires a regular supply of sand, and so I am always filling up plastic bottles to bring back to Vienna in my luggage: in front of the pyramids in Egypt, in the Namib desert, mixed with the shells of small snails or mussels on various Caribbean beaches (which you can recognize and feel on some pictures), and in Tibet on the banks of the Yangtze River. Even my various construction sites have had to serve as a source of sand. And there is a small side effect: The paintings are much heavier than before and the transport of the dried and rolled canvasses from the attic in Zwettl to Vienna for finishing requires strong – masculine! – arms.

In my perception, Linde frequently falls into a shamanistic state while painting. Especially when she is working out in nature or on an “Atelierzeichnung” this restless, energy-charged bundle of impatience is transformed into a state of great relaxation, as if the accumulated information and energy has finally found a outlet by bursting onto the canvas. Linde often says herself that painting is a release of excess life energy. At the start of the act of painting she moves into a transformed, almost medialistic state of mind to align herself with the image to be captured, and recreates the observed and imagined contents of the picture in her uniquely Waberesque cosmos.

NOTES (not to be included in book!)

- “ein rasches Blatt” doesn’t really come across well in the direct translation of “a quick sheet”, so we translated the whole sentence a bit more loosely.

- “Mischtechnik” has a technical definition of “Mischtechnik (mixed technique) is a method of painting where egg tempera is used to build up volume, and is then glazed with oil paints mixed with resin, producing a jewel-like effect.” However, given the previous paragraph, we interpreted the use here to mean “mixed media”, defined as follows “mixed media tends to refer to a work of visual art that combines various traditionally distinct visual art media. For example, a work on canvas that combines paint, ink, and collage could properly be called a „mixed media“ work”

- line 57 in German the cockpit of a sailboat is “Plicht” not “Pflicht”. This should be changed in the original text.

- Line 77 “Partnerschaft” We use the general term “relationship” (~ “Beziehung”), because the more exact translations (e.g. partnership, civil union, common law marriage) all seem too dry or grossly inaccurate.

- Line 83 “Motiv” It seems that the English “motif/motive” has a different meaning from the german term. In English it’s a” repeated pattern or common theme”, so that doesn’t fit with the author’s meaning. We’ve used “focal point” for now, but there should be a better word used by actual artists….

- Line 98 “Schrifttafel” We left this out, assuming the intent is covered by the broader “calligraphy”.